A Closer Look at Big Bend in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania

July 25, 2024

The history of “Big Bend,” located in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, dates back centuries. Its name is a translation of the local Lenape tribe’s description for the dramatic curve along the Brandywine Creek where the property served as a trading post for European settlers. It is believed to have been converted into its present Georgian country manor style by a Scottish general for the crown, whose wife’s correspondence with George Washington about the property can be found in national archives.

When renowned local artist George A. “Frolic” Weymouth purchased the house and surrounding 225 acres in Chadds Ford in 1960, he sought to re-create the original 18th century country manor as closely as possible. The artist’s eccentricities and vivacious character helped make Big Bend a cultural landmark. Following Frolic’s death in 2016, his son, Mac, inherited the property and retained our team as the architect to lead a renovation preparing Big Bend for its new phase as a timeless home for the next generation.

The goal of the historical restoration and renovation to the Chadds Ford property was two-fold. On the exterior, restoration and additions to Big Bend would take place with minimal impact on the historic character of the building in response to a façade easement. Concurrently, as the architect we would completely re-envision the interior of the house through a gut renovation that would deliver amenity updates and a setting for a contemporary lifestyle. The overriding design challenge centered on finding creative but efficient ways to fit the client’s program within the moderately-sized footprint of the house. After a year of design, construction started in August 2018 and concluded three years later.

The New Program

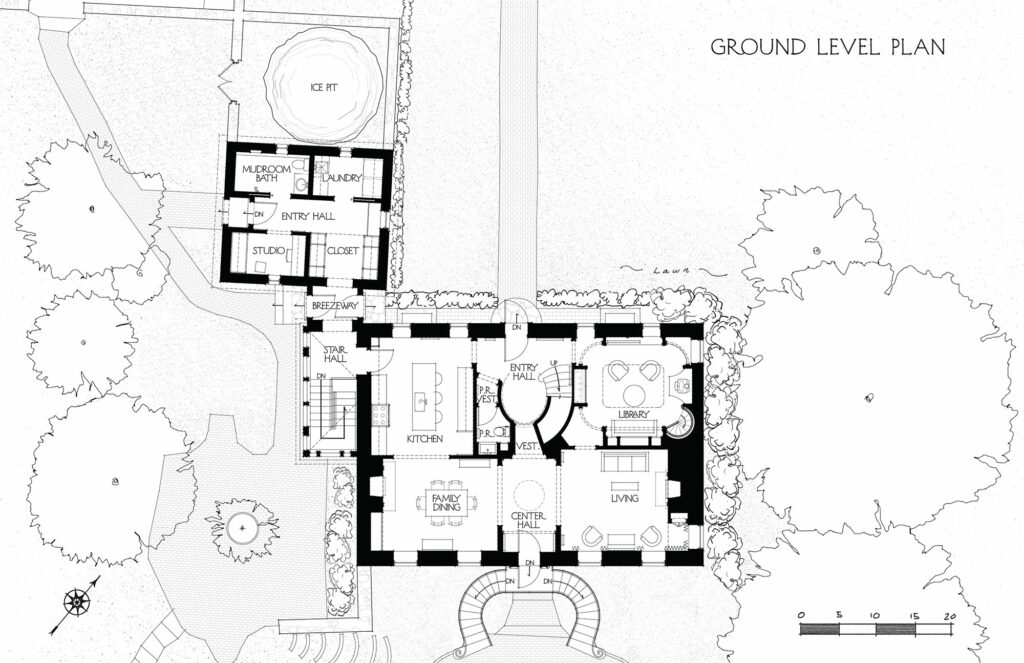

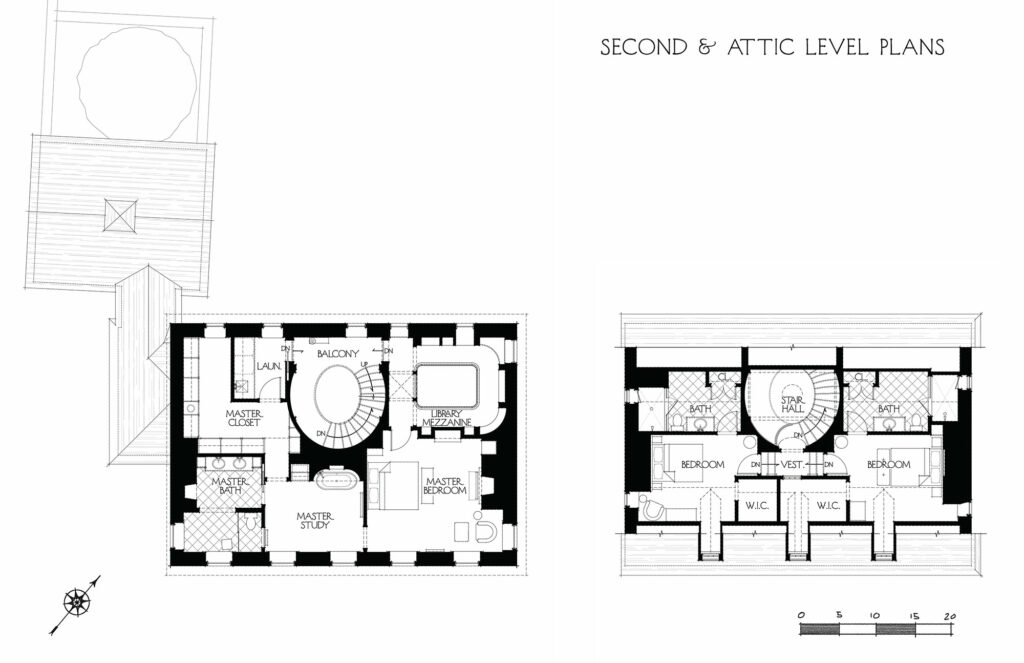

The program for the ground floor of Big Bend included a new family entry and the addition of a modern kitchen. Our client desired a more open floor plan, a double-height library with a mezzanine and a new sculptural stair to replace the existing colonial switchback stair. The entire second floor of the house was to serve as the primary suite while the attic level would house two bedrooms, each with its own full bath.

For the interior architecture, we were granted the latitude to shape and finish spaces using a classical language not directly tied to the previous colonial influenced design. Our client wanted the interior to surprise visitors. In response, our design delivers utterly unique, dramatic spaces created through custom casework, vaulted ceilings, and a plan that provided multiple sightlines through the house from various points of entry.

The focus of the Big Bends’s plan is the new central elliptical stair that maximizes the drama and height of the space within the existing building envelope. Providing access to the second and attic levels, the stair is painted a unique yellow color similar to the existing one, which our client wanted to maintain as a reminder of his childhood home.

The new, double-height library is set in a corner of the house to maximize natural light coming from existing windows on two sides of the house. At the mezzanine level, a delicately arched walkway provides a distinct passage to the master bedroom while maintaining its role in the library’s overall design scheme.

The renovation provided an opportunity to introduce amenities absent throughout Big Bend, some more challenging than others to incorporate. To condition the entire house, a split HVAC was used to save space through a ductless approach. The various wall and floor mounted cassettes are thoroughly planned for in the design and, in many cases, are built into the surrounding millwork with decorative grills to keep them out of sight but easily accessible for regular maintenance.

The extensive ground-floor program required us to expand beyond the already tight footprint of the house proper and incorporate the existing adjacent spring house, previously used as an unconditioned storage/mechanical space, into the ground floor plan as the new family entry space with mudroom, laundry room and dog bath. Additionally, a covered porch was converted into a new lower-level stair hall and linked to the spring house with a diminutive glass breezeway.

The Spring House at Big Bend

The repurposing of the spring house proved difficult in that it did not provide adequate height clearances after its floor level was raised to match the main house; additionally, it lacked windows and was found to be structurally unsound. The solution was drastic but necessary; we demolished the original building and rebuilt a new structure reusing the salvaged masonry as veneer on a conventionally framed and insulated wall construction. The rebuilding of the spring house also allowed us to excavate a basement level beneath it which provided needed storage space within the new, poured concrete foundation.

The original spring house was thoroughly documented prior to demolition which ensured the new construction would match the footprint and facadal character. The building’s raised roof height and added windows made the spring house a functional addition to the house plan. In a bit of theatre, the new veneer was selectively parged and distressed to match the centuries-worn look of the original. A new roof and cupola were installed to match the original in form and materials. The charming stone gable ruin and conical ice pit on the north side of the spring house also were documented, selectively dismantled and then carefully rebuilt.

Other Challenges at Big Bend in Chadds Ford

Vertical connections posed a challenge in the historical restoration and renovation as multiple existing independent stairs to various floor levels consumed critical square footage. Relocating the lower-level stair within the footprint of the existing covered side entry porch provided numerous advantages. We gained space for the new ground-floor kitchen; the new glass enclosure made the progression below grade a light-soaked experience; and the new opening in the house foundation provided a point of circulation to access the home’s oldest room, the lower-level dining room, which was purposefully left in place with as little modification as possible.

Working within the constraints of the existing exterior envelope, multiple existing fireplaces, and the existing exterior window and door layout of the house also posed challenges. This is especially evident in the design of the new double-height library where we implemented a symmetrical rhythm of shelf, paneling and corner cased openings to bring order and proportion to a space lacking consistent vertical alignment of windows. The masonry fireplaces in the new kitchen and library were removed to open up the plan and provide additional floor space. Their removal created structural issues which were creatively resolved through solutions such as the installation of steel platforms in the attic to support the remaining existing chimney masses that were not altered. The exterior doors on the north and south elevations of the house did not share a centerline which we mediated by introducing a funnel-like transition vestibule between the entry hall and stair hall passing under the elliptical stair. These solutions exemplify the unique outcomes possible when working to resolve and order the existing conditions of such a historic building.

The location of the house itself provided a significant challenge in that it was prone to flooding due to its proximity to the Brandywine Creek. We addressed this issue by adding layers of waterproofing and concrete to the interior face lower-level masonry walls. The lower-level door and windows facing the creek were designed to receive interior metal flood gate panels that could be installed when needed through anchors hidden behind removable trim surrounding each opening. In the event of a flood, the entire lower level was engineered to be water-tight up to 6 feet above the finish floor.